Hmong New Year - 2016/2017 - Luang Prabang

- Thread starter DavidFL

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

There are many Hmong groups in Laos & the main ones are

Black Hmong (Hmoob Dub),

Striped Hmong (Hmoob Txaij),

White Hmong (Hmoob Dawb)

Green Hmong (Moob Leeg/Moob Ntsuab)

The Hmong originally came to Laos from China.

The defeat of China by the British in the first opium war (1842) saw the Chinese forced to pay indemnities to the victorious side.

Short of funds to pay, the Chinese raised their own taxes which caused a lot of tension with the minoroties. The Hmong rebelled against the new taxes, & between 1850-1880 lost a series of battles with the Chinese. Consequently they started fleeing southward, with most of them setting in Laos, although some also moved to Vietnam & Thailand.

Then the French came to Laos & also levied taxes.

The Hmong revolted again & there were two major revolts, first in 1896 & secondly in the 1920s. The second Hmong rebellion against the French was lead by Pa Chay, who also called for a Hmong nation & as such remains a hero for many Hmong.

To pacify the Hmong in Laos, the French created an autonomous Hmong district. Eventually 2 clans emerged competing to run the district.

These clans were the Fong & Bliyao clans, but a serious feud broke out in 1922 about who was in control.

In 1938 then the French organized an election for the district chief. The election was won by the son of Fong, Touby Lyfong.

His rival was Faydag Lobliayo, the son of Bliayao.

This rivaly never finished & continued into the Indochina Wars.; Touby Lyfong sided with the French & the the Americans, & Faydang Lobliayao sided with the Lao nationalists, who later became the Pathet Lao.

Black Hmong (Hmoob Dub),

Striped Hmong (Hmoob Txaij),

White Hmong (Hmoob Dawb)

Green Hmong (Moob Leeg/Moob Ntsuab)

The Hmong originally came to Laos from China.

The defeat of China by the British in the first opium war (1842) saw the Chinese forced to pay indemnities to the victorious side.

Short of funds to pay, the Chinese raised their own taxes which caused a lot of tension with the minoroties. The Hmong rebelled against the new taxes, & between 1850-1880 lost a series of battles with the Chinese. Consequently they started fleeing southward, with most of them setting in Laos, although some also moved to Vietnam & Thailand.

Then the French came to Laos & also levied taxes.

The Hmong revolted again & there were two major revolts, first in 1896 & secondly in the 1920s. The second Hmong rebellion against the French was lead by Pa Chay, who also called for a Hmong nation & as such remains a hero for many Hmong.

To pacify the Hmong in Laos, the French created an autonomous Hmong district. Eventually 2 clans emerged competing to run the district.

These clans were the Fong & Bliyao clans, but a serious feud broke out in 1922 about who was in control.

In 1938 then the French organized an election for the district chief. The election was won by the son of Fong, Touby Lyfong.

His rival was Faydag Lobliayo, the son of Bliayao.

This rivaly never finished & continued into the Indochina Wars.; Touby Lyfong sided with the French & the the Americans, & Faydang Lobliayao sided with the Lao nationalists, who later became the Pathet Lao.

Last edited:

A Black Hmong family

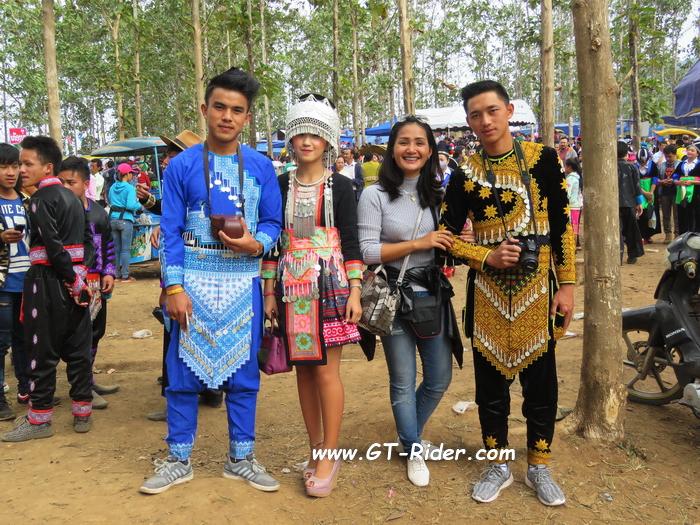

For me a once in a lifetime opportunity for a group photo

10 minutes either way & the group would have broken up.

We asked to join for photos & were warmly welcomed without any hesitation.

Truly wonderful honest people.

Proud of their culture, identity & history.

For me a once in a lifetime opportunity for a group photo

10 minutes either way & the group would have broken up.

We asked to join for photos & were warmly welcomed without any hesitation.

Truly wonderful honest people.

Proud of their culture, identity & history.

Last edited:

Hmong in the Wars

1963

Of the 300,000 Hmong people living in Laos, more than 19,000 men were recruited into the CIA-sponsored secret operation known as Special Guerrilla Units (SGU) while some enlisted as Forces Armees du Royaume, the Laotian royal armed forces. Each soldier was paid an equivalent of three dollars a month. Air America—the “private” airline contracted by the CIA—dropped 40 tons of food per month. King Sisavang Vatthana of Laos appointed Touby Lyfoung to his advisory board.

The US funded new schools throughout the remote regions of Laos, which opened opportunities to Hmong girls. As the war escalated, some Hmong girls were trained as nurses and medics to care for wounded soldiers.

1968-69

In the two worst years of the both the American War in Vietnam and the Secret War in Laos, 18,000 Hmong soldiers were killed in combat, in addition to thousands more civilian casualties. The March 1968 assault by North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao forces on the top-secret airbase at Phou Pha Thi—known to the CIA as “Lima Site 85”—resulted in the deaths of 12 US Air Force personnel, and many more Hmong and Thai soldiers.

By 1969, Hmong troop strength was nearing 40,000. Under the new administration of Pres. Richard Nixon, U.S. bombing of Laos escalated, and Congress learned of CIA covert military operations in Laos.

1971-72

By 1971, the Secret War was weighing heavily on the Hmong and the people of Laos. The estimated death toll for Hmong soldiers this year alone was 3,000, with 6,000 more wounded. More and more boys were becoming involved; the average age of Hmong recruits that year was 15. Throughout 1971, Long Cheng air base was pounded constantly by artillery from massive guns hidden in the surrounding hills. Meanwhile, American opposition to the wars in Southeast Asia mounted, even as Pres. Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger spoke of “peace with honor” and “the light at the end of the tunnel.”

1973

In February, a cease-fire and political peace treaty was signed in Paris, requiring the US and all foreign powers to withdraw all military activities from Laos. More than 120,000 Hmong became refugees in their own homelands. 18,000 Hmong soldiers were left in Laos, representing nearly three-quarters of the irregular forces. About 50,000 Hmong civilians had been killed or wounded in the war.

On September 14, the Vientiane Agreement was signed, giving the Communist Pathet Lao more control of the Lao government.

1975

North Vietnamese Army and Pathet Lao captured Royal Lao positions, and South Vietnam fell to Communist North Vietnam. Gen. Vang Pao and about 2,500 Hmong military forces and family members were airlifted from Long Cheng air base to Thailand. As many as 30,000 other Hmong crowded into Long Cheng, hoping for escape.

By the war’s end, between 30,000 and 40,000 Hmong soldiers had been killed in combat, and between 2,500 and 3,000 were missing in action. An estimated one-fourth of all Hmong men and boys died fighting the Communist Pathet Lao and the North Vietnamese Army. The official US military death total in Vietnam exceeded 58,000.

1975-2015

After overthrowing the Laotian monarchy, the Pathet Lao launched an aggressive campaign to capture or kill Hmong soldiers and families who sided with the CIA. Thousands of Hmong were evacuated or escaped on their own to Thailand. Thousands more who had already gone to live deep in the jungle were left to fend for themselves, which led to the creation of the Chao Fa and Neo Hom freedom fighters movements. Many men also took up arms again to protect their families as they crossed the heavily patrolled Mekong River to safety in Thailand.

Hmong began moving into refugee camps overseen by non-governmental organizations such as the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the International Rescue Committee, Refugees International ,and the Thai Ministry of the Interior. The first Hmong family to resettle in Minnesota arrived in November 1975. The largest wave came after the passage of the US Refugee Act of 1980.

In 2004, the Buddhist monastery at Wat Tham Krabok—the last temporary shelter for 15,000 Hmong remaining in Thailand—closed. This “last wave” came to the US, with as many as 5,000 settling in established Minnesota Hmong communities.

The 2010 census recorded more than 260,000 Hmong in the United States. More than 66,000 of that number lived in Minnesota, most of them in or near the Twin Cities—the largest urban population of Hmong in America.

1963

Of the 300,000 Hmong people living in Laos, more than 19,000 men were recruited into the CIA-sponsored secret operation known as Special Guerrilla Units (SGU) while some enlisted as Forces Armees du Royaume, the Laotian royal armed forces. Each soldier was paid an equivalent of three dollars a month. Air America—the “private” airline contracted by the CIA—dropped 40 tons of food per month. King Sisavang Vatthana of Laos appointed Touby Lyfoung to his advisory board.

The US funded new schools throughout the remote regions of Laos, which opened opportunities to Hmong girls. As the war escalated, some Hmong girls were trained as nurses and medics to care for wounded soldiers.

1968-69

In the two worst years of the both the American War in Vietnam and the Secret War in Laos, 18,000 Hmong soldiers were killed in combat, in addition to thousands more civilian casualties. The March 1968 assault by North Vietnamese and Pathet Lao forces on the top-secret airbase at Phou Pha Thi—known to the CIA as “Lima Site 85”—resulted in the deaths of 12 US Air Force personnel, and many more Hmong and Thai soldiers.

By 1969, Hmong troop strength was nearing 40,000. Under the new administration of Pres. Richard Nixon, U.S. bombing of Laos escalated, and Congress learned of CIA covert military operations in Laos.

1971-72

By 1971, the Secret War was weighing heavily on the Hmong and the people of Laos. The estimated death toll for Hmong soldiers this year alone was 3,000, with 6,000 more wounded. More and more boys were becoming involved; the average age of Hmong recruits that year was 15. Throughout 1971, Long Cheng air base was pounded constantly by artillery from massive guns hidden in the surrounding hills. Meanwhile, American opposition to the wars in Southeast Asia mounted, even as Pres. Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger spoke of “peace with honor” and “the light at the end of the tunnel.”

1973

In February, a cease-fire and political peace treaty was signed in Paris, requiring the US and all foreign powers to withdraw all military activities from Laos. More than 120,000 Hmong became refugees in their own homelands. 18,000 Hmong soldiers were left in Laos, representing nearly three-quarters of the irregular forces. About 50,000 Hmong civilians had been killed or wounded in the war.

On September 14, the Vientiane Agreement was signed, giving the Communist Pathet Lao more control of the Lao government.

1975

North Vietnamese Army and Pathet Lao captured Royal Lao positions, and South Vietnam fell to Communist North Vietnam. Gen. Vang Pao and about 2,500 Hmong military forces and family members were airlifted from Long Cheng air base to Thailand. As many as 30,000 other Hmong crowded into Long Cheng, hoping for escape.

By the war’s end, between 30,000 and 40,000 Hmong soldiers had been killed in combat, and between 2,500 and 3,000 were missing in action. An estimated one-fourth of all Hmong men and boys died fighting the Communist Pathet Lao and the North Vietnamese Army. The official US military death total in Vietnam exceeded 58,000.

1975-2015

After overthrowing the Laotian monarchy, the Pathet Lao launched an aggressive campaign to capture or kill Hmong soldiers and families who sided with the CIA. Thousands of Hmong were evacuated or escaped on their own to Thailand. Thousands more who had already gone to live deep in the jungle were left to fend for themselves, which led to the creation of the Chao Fa and Neo Hom freedom fighters movements. Many men also took up arms again to protect their families as they crossed the heavily patrolled Mekong River to safety in Thailand.

Hmong began moving into refugee camps overseen by non-governmental organizations such as the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the International Rescue Committee, Refugees International ,and the Thai Ministry of the Interior. The first Hmong family to resettle in Minnesota arrived in November 1975. The largest wave came after the passage of the US Refugee Act of 1980.

In 2004, the Buddhist monastery at Wat Tham Krabok—the last temporary shelter for 15,000 Hmong remaining in Thailand—closed. This “last wave” came to the US, with as many as 5,000 settling in established Minnesota Hmong communities.

The 2010 census recorded more than 260,000 Hmong in the United States. More than 66,000 of that number lived in Minnesota, most of them in or near the Twin Cities—the largest urban population of Hmong in America.

A few more happy Hmong New Year snaps

Time to go home

You meet the nicest people on a Honda..

Cheers

I hope some of you guys liked this little Hmong New Year journey.

Hmong New Year has featured on GTR before here.

Phonsavan is the best place to go in Laos for Hmong New Year. Witnessed by Moto-Rex

Hmong New Year celebrations. Phonsavan Laos.

Luang Prabang

Hmong New Year - Luang Prabang - December 2015

In & around Chiang Mai they have a Hmong Formula Hmong cart racing, witnessed by Jurgen

Formula Hmong cart racing

Mae Sa Valley Chiang Mai

Hmong New Year Nong Hoi Mai Mae Khi

Time to go home

You meet the nicest people on a Honda..

Cheers

I hope some of you guys liked this little Hmong New Year journey.

Hmong New Year has featured on GTR before here.

Phonsavan is the best place to go in Laos for Hmong New Year. Witnessed by Moto-Rex

Hmong New Year celebrations. Phonsavan Laos.

Luang Prabang

Hmong New Year - Luang Prabang - December 2015

In & around Chiang Mai they have a Hmong Formula Hmong cart racing, witnessed by Jurgen

Formula Hmong cart racing

Mae Sa Valley Chiang Mai

Hmong New Year Nong Hoi Mai Mae Khi

Last edited:

Lovely pictures from wonderful people - this year Laos was probably the place to be as many réjouissances were suppressed in Thailand for mourning reasons

An interesting story on Hmong New Year from a Vietnamese publication.

I have no doubt in the more remote areas in Laos towards the VIetnam border these traditions are still carried on...

Read on..

I have no doubt in the more remote areas in Laos towards the VIetnam border these traditions are still carried on...

Read on..

Alpine ethnic people in Vietnam – P5: ‘Wife-pulling’ custom

Many young ethnic Mong have tied the knot after receiving taps on the buttocks, waists or even genitals from the partner they are flirting with

Whether or not the custom is obsolete or inappropriate in today’s world, ‘pulling a wife,’ a deeply-rooted practice of Mong ethnic men, remains a unique cultural trait of the community.

The custom is traditionally observed by the Mong who inhabit several districts in the northern province of Ha Giang.

According to the practice, a man who wishes to marry a girl he loves must be able to ‘catch’ her and bring her to his house in order for the wedding to take place.

Traditionally, the ‘pulling a wife’ ritual is just for show, as most couples would have already consented to the marriage beforehand, and the girl would fake resisting her lover’s grip to add to the drama.

Alternatively, the custom is also of great help to couples whose parents oppose the marriage, as once the girl has been ‘kidnapped’ and brought to the man’s house, she can no longer be rejected by his family.

In springtime, particularly at Lunar New Year festivals, paths meandering around rugged rocks across the UNESCO-recognized Karst Plateau, are frequented by groups of young Mong men and girls, who dress their best in traditional costume.

This is also a time when many young couples will practice the custom and find their lifelong partner.

Inside a ‘stone fortress’ perched on the flank of the Ma Pi Leng Pass, Mua Thi Mai held her baby and stared at the gaping abyss near the thread-like Nho Que River beneath, as if it represented her unknown future.

The pass, at the heart of Dong Van Karst Plateau and one of the northern region's most spectacular, snakes its way through Meo Vac District.

Five years ago, when she was just 17, Mai, in her most beautiful traditional dress, went to a spring festival in the neighborhood alone.

At the event, she was ‘pulled’ by Li Mi Sing to his home to officially become his bride.

The couple had fallen in love before and made an arrangement for the ‘pulling wife’ custom to happen at the springtime festival.

Three days later, Sing’s family sent a representative to let Mai’s parents know she was now their son’s wife and their daughter-in-law.

Despite holding a small nuptial ritual at the time, the two families and the couple have yet to throw an official wedding celebration five years later.

Similarly, Vu Mi Tuan and Sung Thi Mai, who reside in Lung Phin Commune in Dong Van District, have given birth to two children, with the eldest now eight years old.

However, their wedding plans remain elusive.

Tuan ‘pulled’ Mai at a springtime market session in Lung Phin Commune around 10 years ago.

It is the norm in Mong culture that couples with children delay holding the wedding until they have enough money.

According to researchers, Mong’s long-standing marriage custom can be finely divided into ‘pulling,’ ‘catching’ and ‘stealing’ wives.

With regard to ‘pulling a wife,’ couples usually date and make an arrangement at crowded places, particularly at spring festivals, for the men to take their women to their home as wives.

‘Wife catchers’ will ask any girl of their choice to become their wives regardless of the girls’ consent, and agree to give exorbitant dowries.

Several young men in northern Vietnam have abused the seemingly harmless tradition, arguing that the ritual grants them the right to make any girl their wife as long as they can successfully bring her home.

‘Wife stealers,’ meanwhile, try to steal or talk the girls who they fall for into eloping with them even though the girls have already become engaged or even married.

Only ‘pulling a wife’ lingers in today’s world, while ‘wife catching’ and ‘wife stealing’ practices have been on the decline.

Whatever the form, the bridegrooms’ parents are elated when their sons get married.

Despite their own and their parents’ discontentment, brides are considered ‘their in-laws’ ghosts’ after the in-laws move a cock in a circle three times above the couples’ heads.

(White) Mong residing in Lung Pu Commune, Meo Vac District also choose to flirt with their potential partners in a bottom-tapping fest by patting on their bottom or waist.

If the act is reciprocated by a tap from the girls, the couples will have a matchmaker talk to the parents on both sides, and they will be allowed to wed.

During the event, the youths can also pat their partners’ private parts, an act that will not be considered obscene.

Aside from these customs, Mong bridegrooms’ families typically present hefty conjugal dowries including money, jewelry, cattle, wine and clothes to the brides’, despite the couples being still minors.

Da Di Mua, 26, and his wife Da Thi Dinh are an example of this conjugal dowry tradition.

The young lovebirds already have three children, with the eldest being 10.

“Twelve years ago, when I was only 14, my parents found my wife for me. She was 19 then and was five years older than me. Her family accepted our hefty conjugal dowry,” Mua shared.

The ‘wife pulling’ and ‘nuptial challenge’ practices have also brought about undesired consequences, including child or premature marriages, and a lack of understanding between lovers due to the limited opportunity to get to know each other.

A large number of young Mong women have resorted to chewing ‘la ngon’ (a fatally poisonous leaf) in suicide attempts after a short time living with their in-laws.

Statistics by agencies reveal that in recent times, young women have broken away from their in-laws shortly after their marriage, with the in-laws mobilizing people to bring the ‘runaway brides’ back.

Melancholic songs about local women’s miserable married lives have become a major part of the Mong folk heritage.

Sung Dai Hung, director of the Ha Giang Department of Labor, War Invalids and Social Affairs and a Mong native in Dong Van District, is strongly supportive of the ‘pulling a wife’ practice, which he still deems humanitarian.

“The substantial conjugal dowries have proven out of reach for poor Mong families. The ‘pulling a wife’ practice thus ensures youths’ freedom to seek love and rich men’s chance to marry the girls of their dreams,” he observed.

“However, underage youngsters, who are only 15 or 16, should not ‘pull’ wives and tie the knot,” he noted.

Tuoi Tre News. Vietnam. June 19,2017.

Many young ethnic Mong have tied the knot after receiving taps on the buttocks, waists or even genitals from the partner they are flirting with

Whether or not the custom is obsolete or inappropriate in today’s world, ‘pulling a wife,’ a deeply-rooted practice of Mong ethnic men, remains a unique cultural trait of the community.

The custom is traditionally observed by the Mong who inhabit several districts in the northern province of Ha Giang.

According to the practice, a man who wishes to marry a girl he loves must be able to ‘catch’ her and bring her to his house in order for the wedding to take place.

Traditionally, the ‘pulling a wife’ ritual is just for show, as most couples would have already consented to the marriage beforehand, and the girl would fake resisting her lover’s grip to add to the drama.

Alternatively, the custom is also of great help to couples whose parents oppose the marriage, as once the girl has been ‘kidnapped’ and brought to the man’s house, she can no longer be rejected by his family.

In springtime, particularly at Lunar New Year festivals, paths meandering around rugged rocks across the UNESCO-recognized Karst Plateau, are frequented by groups of young Mong men and girls, who dress their best in traditional costume.

This is also a time when many young couples will practice the custom and find their lifelong partner.

Inside a ‘stone fortress’ perched on the flank of the Ma Pi Leng Pass, Mua Thi Mai held her baby and stared at the gaping abyss near the thread-like Nho Que River beneath, as if it represented her unknown future.

The pass, at the heart of Dong Van Karst Plateau and one of the northern region's most spectacular, snakes its way through Meo Vac District.

Five years ago, when she was just 17, Mai, in her most beautiful traditional dress, went to a spring festival in the neighborhood alone.

At the event, she was ‘pulled’ by Li Mi Sing to his home to officially become his bride.

The couple had fallen in love before and made an arrangement for the ‘pulling wife’ custom to happen at the springtime festival.

Three days later, Sing’s family sent a representative to let Mai’s parents know she was now their son’s wife and their daughter-in-law.

Despite holding a small nuptial ritual at the time, the two families and the couple have yet to throw an official wedding celebration five years later.

Similarly, Vu Mi Tuan and Sung Thi Mai, who reside in Lung Phin Commune in Dong Van District, have given birth to two children, with the eldest now eight years old.

However, their wedding plans remain elusive.

Tuan ‘pulled’ Mai at a springtime market session in Lung Phin Commune around 10 years ago.

It is the norm in Mong culture that couples with children delay holding the wedding until they have enough money.

According to researchers, Mong’s long-standing marriage custom can be finely divided into ‘pulling,’ ‘catching’ and ‘stealing’ wives.

With regard to ‘pulling a wife,’ couples usually date and make an arrangement at crowded places, particularly at spring festivals, for the men to take their women to their home as wives.

‘Wife catchers’ will ask any girl of their choice to become their wives regardless of the girls’ consent, and agree to give exorbitant dowries.

Several young men in northern Vietnam have abused the seemingly harmless tradition, arguing that the ritual grants them the right to make any girl their wife as long as they can successfully bring her home.

‘Wife stealers,’ meanwhile, try to steal or talk the girls who they fall for into eloping with them even though the girls have already become engaged or even married.

Only ‘pulling a wife’ lingers in today’s world, while ‘wife catching’ and ‘wife stealing’ practices have been on the decline.

Whatever the form, the bridegrooms’ parents are elated when their sons get married.

Despite their own and their parents’ discontentment, brides are considered ‘their in-laws’ ghosts’ after the in-laws move a cock in a circle three times above the couples’ heads.

(White) Mong residing in Lung Pu Commune, Meo Vac District also choose to flirt with their potential partners in a bottom-tapping fest by patting on their bottom or waist.

If the act is reciprocated by a tap from the girls, the couples will have a matchmaker talk to the parents on both sides, and they will be allowed to wed.

During the event, the youths can also pat their partners’ private parts, an act that will not be considered obscene.

Aside from these customs, Mong bridegrooms’ families typically present hefty conjugal dowries including money, jewelry, cattle, wine and clothes to the brides’, despite the couples being still minors.

Da Di Mua, 26, and his wife Da Thi Dinh are an example of this conjugal dowry tradition.

The young lovebirds already have three children, with the eldest being 10.

“Twelve years ago, when I was only 14, my parents found my wife for me. She was 19 then and was five years older than me. Her family accepted our hefty conjugal dowry,” Mua shared.

The ‘wife pulling’ and ‘nuptial challenge’ practices have also brought about undesired consequences, including child or premature marriages, and a lack of understanding between lovers due to the limited opportunity to get to know each other.

A large number of young Mong women have resorted to chewing ‘la ngon’ (a fatally poisonous leaf) in suicide attempts after a short time living with their in-laws.

Statistics by agencies reveal that in recent times, young women have broken away from their in-laws shortly after their marriage, with the in-laws mobilizing people to bring the ‘runaway brides’ back.

Melancholic songs about local women’s miserable married lives have become a major part of the Mong folk heritage.

Sung Dai Hung, director of the Ha Giang Department of Labor, War Invalids and Social Affairs and a Mong native in Dong Van District, is strongly supportive of the ‘pulling a wife’ practice, which he still deems humanitarian.

“The substantial conjugal dowries have proven out of reach for poor Mong families. The ‘pulling a wife’ practice thus ensures youths’ freedom to seek love and rich men’s chance to marry the girls of their dreams,” he observed.

“However, underage youngsters, who are only 15 or 16, should not ‘pull’ wives and tie the knot,” he noted.

Tuoi Tre News. Vietnam. June 19,2017.