1. Introduction

A visit to the small “Tai Dam” community in Ban Na Pa Nat, near to Chiang Khan, in Loei province, provides a unique cultural insight in a less known ethnic group. In times of uniformization, efforts made to keep traditions alive are laudable and well worth to be supported.

Before relating my calls to this village, I would like to provide a short disambiguation and highlight these people’s long migration history.

The appellation “Tai” refers to an ethnic group belonging to a language family, while the term “Thai” refers to a nationality, to the citizens of Thailand. The latter is relatively recent, as this country name was coined, in 1939, under Premier Phibun Songkhram, in order to replace “Siam”.

A couple of thousand years ago, Tai ethnic people can be traced to South-East China, as far as Shanghai; prior to this, their origin is not precisely known. Later on, they are believed to be the settlers of Nanzhao (South-West China) and, as their empire declined, they moved south, to today’s Yunnan, North-East Burma, Laos, North Thailand and, down the Chao Phraya river, into Thailand’s central plains (more information in endnote [1]).

The Tai Dam people participated to this migration and established themselves in North Vietnam, founding a kingdom called “Sipsong Chu Thai”. Muang Thaeng, currently Dien Bien Phu, was their capital. During the French colonization, it was first incorporated into Tonkin, then into the autonomous “Tai Federation” and, finally, after the "Geneva Agreements", attached to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. This community calls itself “Black Tai” (Tai Dam) in reference to their clothing, which, for the main part, is dark.

Tai Dam women in traditional black attire and embroidered headdress.

“Black Tai” women wearing a traditional embroidered headdress.

In the eighteens and nineteens century a part of the “Sipsong Chu Thai” population was displaced to populate Siam and, with the last century’s Indochina turmoil, many “Black Tai” fled their homeland and migrated to Laos, Thailand, or were granted asylum in the American state of Iowa. In Thailand, the early immigrants are usually called “Lao Song (Dam)”, while the newcomers, as in Ban Na Pa Nat, keep their “Tai Dam appellation”.

Tai Dam lady with black headdress.

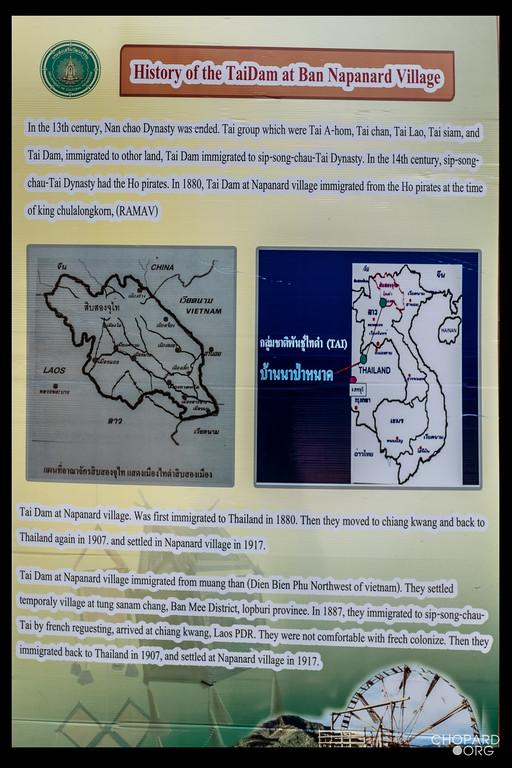

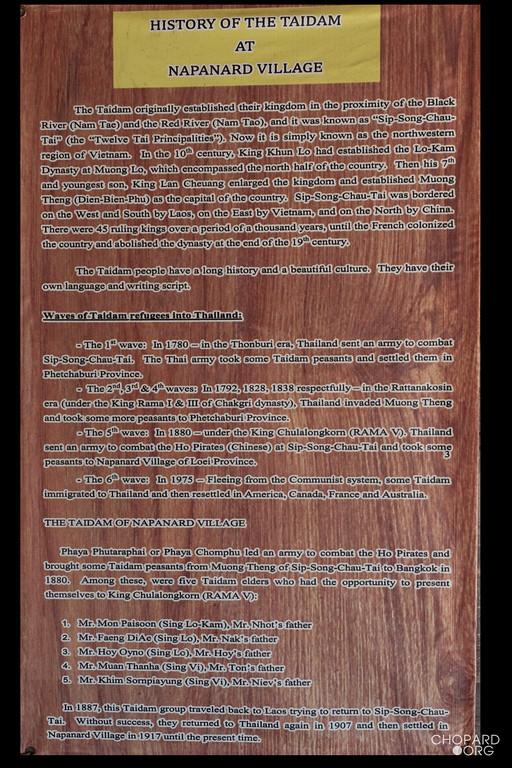

The Tai Dam migration history is summarised on panels displayed at the “Ban Na Pa Nat” cultural centre [2]):

[SIC]: “In the 13thcentury, Nan Chao Dynasty was ended. Tai groups which were Tai A-hom, Tai Lao, Tai Siam and Tai Dam emigrated to other land, Tai Dam emigrated to Sip Song Chau Tai. In the 14thcentury, sip-song-Chau-Tai had the Ho pirates. In 1880, Tai Dam at Napanard village emigrated from the Ho pirates at the time of king Chulalongkorn (Rama v).

Tai Dam at Napanard village first immigrated to Thailand in 1880. Then they moved to Chiang Kwang and back to Thailand again in 1907 and settled in Napanard village in 1917.

Tai Dam at Napanard village immigrated from Muang Than (Dien Bien Phu Northwest of Vietnam). They settled temporarily village at Tung Sanam Chang, Ban Mee district, Lopburi province. In 1887, they immigrated to Sip-Song-Chau Tai by French requesting, arrived at Chiang Kwang, Laos PDR. They were not comfortable with French colonie. They immigrated back to Thailand in 1907, and settled at Napanard village in 1917”

One of the information panels in Ban Na Pa Nat.

2. The Road to Ban Na Pa Nat

The Tai Dam village of “Na Pa Nat” is located in North-East Thailand’s Loei province. It is close to Chiang Khan, a lively Mekong rim village, at the crossroad of three itineraries. The first trail follows the Mekong, north from Nong Kai, the second drives straight down from Loei city and the third, the western itinerary, crosses the “Door of Isan” in Dansai and leads down to Tha Li (the border crossing to Laos), then along the Hueang and Mekong rivers.

A “Phi Ta Khon” mask greeting travelers at the “Door of Isan”, just before Dansai.

For travelers on motorcycles, but also for car drivers, the region offers a maze of exhilarating rollercoasters through tree covered hills and a wealth of coiling trails along rivers.

Rollercoasters down to Tha Li and Chiang Khan.

Rollercoasters down to Tha Li and Chiang Khan.

Lively Chiang Khan along the Mekong river rim.

Many visitors spend a night or two in Chiang Khan, to enjoy the Mekong river’s mood and for an evening ramble through the city’s lively walking street. It is also a convenient starting point for a call to the nearby Tai Dam village.

Sunset mood along Chiang Khan’s Mekong promenade.

Early evening along the Mekong rim

Strolling through Chiang Khan’s walking street

A lively city, particularly in the evening hours.

Chiang Khan’s illuminated walking street.

The Tai Dam village of Na Pa Nat is only twenty-six kilometres away from Chiang Khan’s city centre. The itinerary starts with six kilometres on Route 201 (toward Loei), followed by twenty kilometres on provincial Route 3011.

Intersection of Route 201 and Route 3011 toward Ban Na Pa Nat.

3. Tai Dam House of Museum.

The first point of interest, when arriving in Ban Na Pa Nat is a cultural showcase: “The Tai Dam house of Museum”. It is one of the four places in the village built up to keep the culture alive for the next generation and promote it to visitors; they all feature weaving demonstrations and traditional buildings.

Now-a-days, this village has about five hundred inhabitants whose ancestors immigrated, more than one hundred years ago. After misfortunes in nearby hamlets, they finally choose a place located near to a forest of crabapple trees (nat trees) who have a camphor smell, disliked by spirits; actually, “Ban Na Pa Nat” literally means “the village near to the crabapple forest” [3].

Even so they originate from the same ethnic group, and region, the people of Ban Na Pa Nat are distinct from the “Lao Song (Dam)” of other Thai provinces. The latter arrived in the eighteens and nineteens century, particularly under the reign of king Chulalongkorn (Rama V) and were forced to populate Siam. The dwellers of Na Pa Nat arrived more recently, after the Indochina turmoil; they were able to keep their traditions largely alive and are known under their original name “Tai Dam”. Some of these settlers still have relatives in North Vietnam.

Modernization and economic growth take heavy tributes on traditions, particularly in smaller communities. While Thai-ness was promoted as an acculturation process, efforts are made, these days, to save the eroding cultural heritages. These are not only touristic assets but indispensable identity markers, linking individuals and groups to their roots.

The Tai Dam community in Na Pa Nad is committed to keep alive part of their culture, traditions and believes, providing a unique insight for visitors. Travelers to this village are not always aware of ethnic treasures on display, not only in form of antic artefacts and buildings, but through actual performances in daily life, ceremonies and festivals.

Billboard and main museum building at the “Tai Dam House of Museum”.

Some practices are common to most Tai groups. For instance, the houses used to be made with bamboo, covered with tree leave roofs, and were built on stilts; wetland rice cultivation provided the main staple and clothing was made by weaving cotton. Contemporary dwellings are more and more built with bricks, rice remains important, but in all communities, clothes, for daily use, are seldomly produced locally.

The aim of Na Pa Nat dwellers is to keep, as much as possible, their cultural heritage and traditions in their modern life. However, ancient houses are now only built as showrooms or “homestay” lodgings, while skilled weaver still produce cotton and silk artworks, traded to bring some revenues.

Small Tai Dam traditional constructions reproductions.

Tai Dam rice storing buildings.

Upper room of a traditional Tai House, now used as a museum.

A “Black Tai” lady wearing a traditional dress.

A Tai dam lady in a traditional attire.

The clothes play important roles in the Tai Dam’s ethnic identity. The group’s name refers to their custom to wear black attire, a society identification mark, a link to the ancestors and a sign of recognition when reaching “Muang Fa”, their heavenly realm. Silver adornments are also part of the costume, for instance earrings, hairpins, necklaces and belts.

A traditional “Black Tai” silver “butterfly clasp”.

An embroidered headdress scarf, the main colour spot in a Tai Dam women’s dress.

4. Weaving group “hamlet 12”

Another point of interest, in Ban Na Pa Nat is the “Weaving Group Center of Hamlet 12” (Moo 12). The place features some traditional buildings, a weaved cloths shop with an exhibition and a couple of wooden frame looms used by skillful women to produce silk and cotton pieces of art. Here, this important craft is kept alive while allowing dwellers to earn an income. The survival of this handiwork depends on its commercialization, on the possibility for the next generation to earn a living through it, and the readiness to embrace this artisanal profession.

Entrance to “Moo 12 Weaving Group”.

Khun Pa Pen, the most skilled Tai Dam weaver in Na Pa Nat.

Khun Sopha, a skilled daughter of Khun Pa Pen, working on a frame loom.

Khun Wipa, another member of the famous Na Pa Nat weaving family.

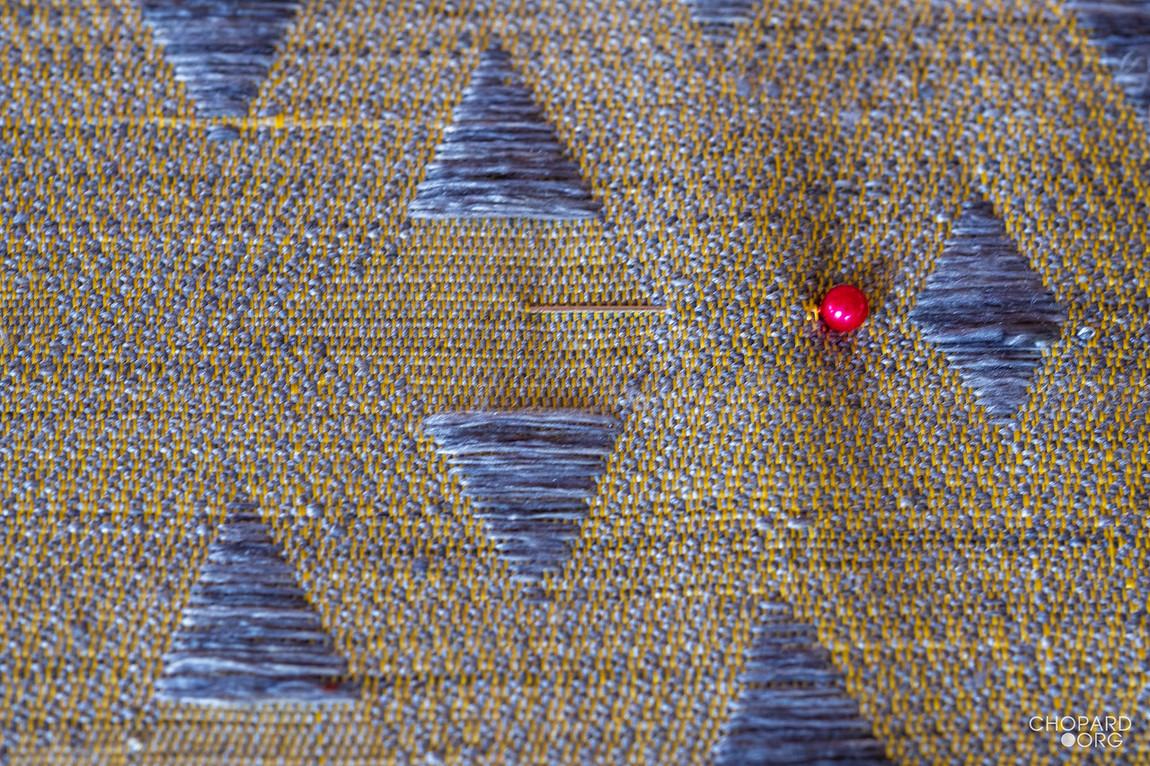

The traditional Tai Dam weaving tools are “frame looms”. The family in hamlet 12 is highly skilled and able to produce pieces with as many as 50 lines. The silk artwork on the loom, at the time of my visit, had 25 lines, a high weaving density, with a daily output of only thirty centimeters. The finished product, a special order for an American actress, will have a length of four meters. The daily output, for the even higher density weavings of 50 lines, is just twelve centimetres.

A 25 lines piece of art in progress, weaved on a frame loom by Khun Sopha.

Detail of the weaving piece in production, the red needle head shows the scale of the pattern.

The “Tai Dam flowers” are traditional decorations with protective powers. They are made out of shiny yarns and bamboo sticks, in various shapes. The cube brings good fortune, but the most popular form is the “Tum Noo Tum Nock” (mouse and bird box), shaped like a house, and used to protect dwellings from evils. They are usually mounted as mobiles, in different sizes.

Colorful yarn and bamboo decoration (Tai Dam flower).

A disappearing craft is the handweaving of baskets, which, in the past was the competence of men. In Na Pa Nat, plaited objects are no longer produced permanently, but demonstrations might be organized during festival times.

A Tai Dam man plaiting a colourful basket.

5. The annual brotherly reunion

The third place of interest is the village is the “Tai Dam Cultural Center”, opened in 1996 to preserve and showcase the “Black Tai” traditions and way of life.

On April 6th, every year, the Ban Na Pa Nat community organizes a festival called “Fraternal Tai Reunion”, inviting acquaintances and visitors to celebrate in a traditional way and to fulfill rituals for ancestors and spirits. This date was chosen to coincide with the “Chakri Day”, a national holiday in Thailand, allowing more people to participate to the venue.

During the morning, stalls are setup, collective food is prepared, and the place is arranged for the festival. Games are also organized for children and weavers demonstrate how to spin cotton threads, while small makeshift shops sell local products.

The center of the festivities is the “Ton Pang” a tree adorned with a variety of flashy mobiles featuring the traditional Tai Dam decorations in various shapes; they are globally called “flowers” (dok mai Tai Dam).

A decorated tree (Ton Pang) marks the center of the festivities place.

The traditional “Black Tai” decorations, the “Tai Dam flowers”, are omnipresent.

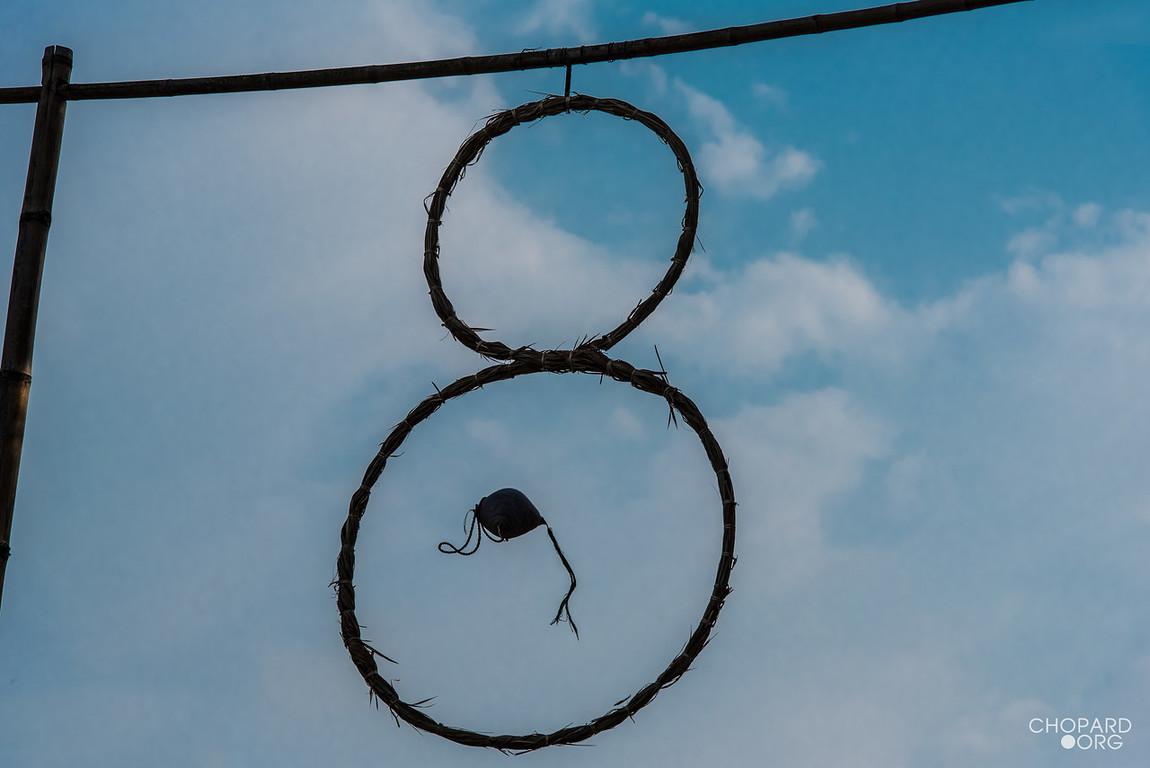

The first activities during the morning, are children’s games and competitions, like walking on stilts and throwing cloth balls through a suspended figure eight target (tot ma kon).

Kids in Tai Dam dresses play around the festival compound.

Walking on stilts, a children’s game.

Throwing cloth balls through a target (tot ma kon), a competition for kids and adults.

Tai Dam girls performing traditional dances.

The official opening is at noon, usually with the presence of high ranking representatives from the province and, as in 2018, the presence of “Miss Grand Thailand Loei 2018”, a charming crowned princess, available for selfies or children’s group pictures.

Speeches and other performances are presented on a podium or on the central place, around the decorated pole (Ton Pang).

Opening ceremony on the podium.

Opening ceremony and speeches.

The podium also serves as a catwalk for “Black Tai” dwellers in traditional attire.

The rhythms accompanying Tai Dam music and dances, are produced by large hand-held bamboo trunks, hit on floor planks; these cavernous sounds are echoed by percussions on metallic gongs.

Tai Dam ladies with rhythmic bamboo trunks.

A line of “Black Tai” ladies holding bamboo trunks.

Colorful stitched Tai Dam headdress.

“Black Tai” ladies in traditional attire.

Tai Dam ladies on stage.

On stage with a traditional headdress.

“Black Tai” ceremony on the central place.

Group pictures on the central place.

“Miss Grand Loei 2018”, a charming crowned princess.

Miss Grand Loei 2018 – visiting the “Black Tai” venue.

In the early evening, a parade is organized along the village’s main road. It is a slow-moving cortege, as many participants are dancing all along the way.

Dancing “Black Tai” pageants.

Tai Dam cortege participants.

Sitting on decorated chariots – a relaxed way to attend the procession.

Tai Dam ladies sitting on a parade chariot – they wear black tube-skirts with a traditional watermelon pattern (sin taeng moo).

A young pageant hanging on his mother’s back in a traditional way.

Finally, the cortege reaches the festival place, and the rest of the evening is devoted to traditional dances around the decorated tree (Ton Pang).

Traditional dances on the on the central place.

6. people and traditions

The Tai Dam people of Ban Na Pa Nat are committed to maintain whatever possible from their cultural heritage. Compared to other ethnic groups, they have done well and are recognized for this achievement. This is, however, not an easy endeavour as, for many years, integration and acquisition of Thai-ness was the political aim.

Development and modernity are, nowadays, the eroding factors for traditions; in order to make choices and to increase the economic levels, external exposure and knowledge acquisition is necessary. Particularly youngsters are leaving the community for environments were uniformization is required. Currently, western type habiliments are the norm, not only to dwell outside but also in the village itself. Clothing remains an important identity marker for the Black Tai, a link to their roots and ancestors, as well as a recognition sign for the next realm; in Ban Na Pa Nat the villagers still take many opportunities to wear their traditional attires, for special festivities, as it is the case for the annual “Fraternal Tai Reunion”.

The clothes play important roles in the Tai Dam’s ethnic identity. The group’s name refers to their custom to wear black attire, a society identification mark, a link to the ancestors and a sign of recognition when reaching “Muang Fa”, their heavenly realm. Silver adornments are also part of the costume, for instance earrings, hairpins, necklaces and belts

Traditional “Black Tai” attire

Colorful stitched scarf headdress

Despite common roots, the Tai Dam language is quite different and not mutually intelligible for central Thai inhabitants. In addition to their own idiom, youngster have to learn “central Thai” (at school) and probably some Isan language (Lao). In the village itself the Tai Dam language is still widely spoken.

Group picture in various outfits.

Tai Dam lady in traditional attire.

Tai Dam lady in traditional attire.

The specific Tai Dam script, is rarely used now. Seen from afar it shows similarities with the Thai or Lao scripts; it is, however, totally different and illegible for untrained eyes.

Tai Dam lady in traditional attire.

Tai Dam lady in traditional attire.

Young Tai Dam girl.

Hair is an important feature for “Black Tai”, they keep it long and tie it into knots indicating their marital status.

Tai Dam ladies preparing their hair for the festival.

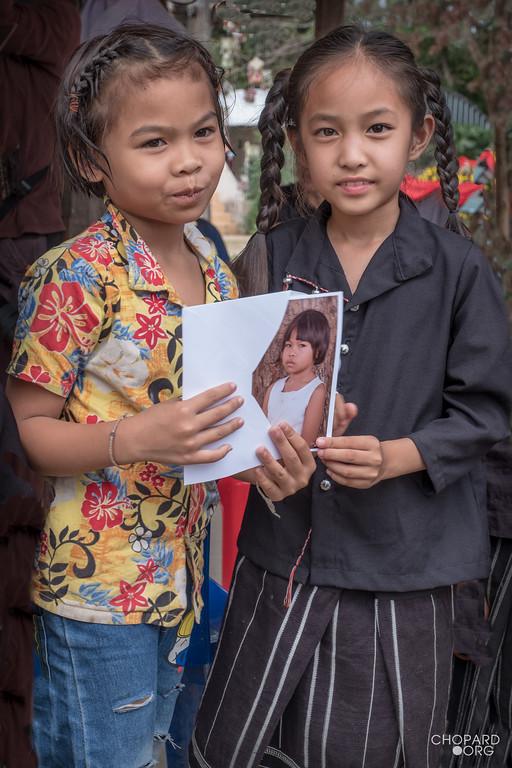

When I go back to villages that I have visited in the past, I print some pictures and give them to my former “models”. I did this in Na Pa Nat and handed out photographs taken the year before.

Group of young “Black Tai” girls with pictures from last year.

A young Tai Dam girl, together with a friend, holds her picture from last year.

7. Beliefs and funerals

In their homeland, in North Vietnam, the Tai Dam are mostly animist, a differentiation from the other Tai groups. In Ban Na Pa Nat this has to be put in perspective as, currently, a majority of the inhabitants are nominally Buddhists, with a small number of Christians. Nevertheless, and as it is the case in other communities in Thailand, Brahmanism, animism and ancestral worship are intermingled in daily life’s practices. Spirits (phi) still play an important role in Thailand’s folk imagination; this is the case in the “Black Tai” community with animism and Brahmanism being very present.

During one of my visits to Na Pa Nat, I was invited to participate in a traditional funeral, and was advised that it would be similar to a Christian ceremony.

The traditional Tai Dam funerals are officiated by a shaman (moo phi) [4] and the corpses are entombed in a sacred forest near to the village. A walking cortege of dwellers, family and friends of the deceased, process toward the burial place, with, these days, a pick-up truck transporting the coffin.

The funeral procession led by the shaman from the village to the sacred forest.

Once the Shaman has defined the precise burial place, villagers take turns to excavate a pit, about as deep as a standing person.

Villagers taking turn to excavate a pit.

As the soil is sandy, the work is progressing rapidly.

The pit is about the depth of a standing person.

Last inspection of the pit by the shaman.

Friends and relatives are waiting near to the excavation work.

Relatives with a picture of the deceased loved one.

The “Black Tai” cultural link to their clothing remains behind their death. The deceased person is dressed in its Tai Dam attire for his burial, in order be recognized in “Muang Fa”, their heavenly realm.

The corpse is displayed one more time, allowing relatives to bid a last farewell, and spray holly water on the deceased face.

The burial procedure is supervised by the shaman.

A relative at the burial place.

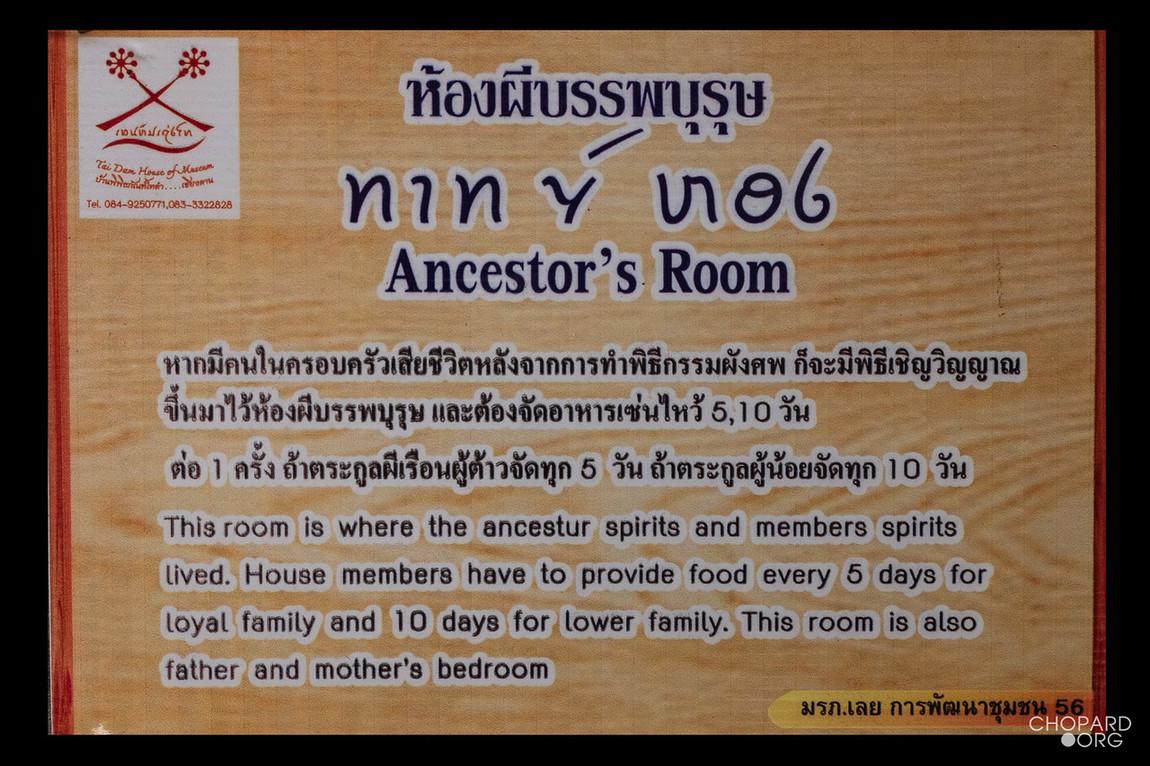

After the funerals, the deceased spirit is invited to dwell into a special room (Ancestor’s Room), located in the residence house.

In the museum: explanatory board written in Thai and English – the second line is “Black Tai” script.

------------

Notes:

[1] The Tai origin and migration history is more complex and uncertain than outlined in my shortcut. In contrary to the Chinese history, no written early Tai chronicle exists, and the oral transmission, often legendary, leaves many points unclarified. It seems, however, that the Tai and Chinese shared common roots which, for unknown reasons, split in different directions.

The early Tai societies were organized in “muangs”, small people conglomerates, normally located in a single valley and led by a chieftain. With the time, some “muangs” gained strength, were able to build alliances with neighbors, and, finally, became principalities or kingdoms. The shape and fate of these larger entities was molded by their own strength and ambitions, but also through geopolitics, like the Mongol invasions, the activities of Haw bandits, the Burmese and Khmer war appetites, the developments of China, and finally, the French and British colonial occupations and their backlashes.

This sketchy historical shortcut is only meant to put the global Tai migrations into a frame. Nowadays, Tai ethnic people are found, in various percentages, in Thailand, Laos, Burma, Vietnam, China and Northeast India. In Thailand and Laos they are the majority of the population while in other countries, their former kingdoms were integrated, leaving them as national minorities (Shan, Tai Lue, Black Tai, Puan, …)

[2] [SIC] this is the original text transcription, only slightly adapted for gross language mistakes.

[3] Wikipedia: Blumea balsamifera is a flowering plant belonging to the Blumea genus, Asteraceae family. It's also known as Ngai camphor and sambong (also sembung). In Thai folklore, it is called Naat (หนาด) and is reputed to ward off spirits.

[4] I use the name “shaman” as it is the most common for Westerner. Actually, in this case it is a “Mo Phi” which translates as “(spirit) priest”. The Tai Dam have a whole hierarchy of religious practitioners, who, usually transmit their powers and knowledges in a hereditary lineage. The actual Tai Dam Shaman is called “Mo Mod”.

Some literature:

Tai Groups of Thailand

Volume 1 Introduction and Overview

Joachim Schliesinger

2001 White Lotus, Bangkok

The Thai Ethnic Community in Viet Nam

Cam Trong

The Gioi Publishers 2007, Vietnam

Dress and Identity among the Black Tai of Loei Province Thailand

Franco Amantea

Thesis Bachelor of Arts, Simon Fraser University 2003

A visit to the small “Tai Dam” community in Ban Na Pa Nat, near to Chiang Khan, in Loei province, provides a unique cultural insight in a less known ethnic group. In times of uniformization, efforts made to keep traditions alive are laudable and well worth to be supported.

Before relating my calls to this village, I would like to provide a short disambiguation and highlight these people’s long migration history.

The appellation “Tai” refers to an ethnic group belonging to a language family, while the term “Thai” refers to a nationality, to the citizens of Thailand. The latter is relatively recent, as this country name was coined, in 1939, under Premier Phibun Songkhram, in order to replace “Siam”.

A couple of thousand years ago, Tai ethnic people can be traced to South-East China, as far as Shanghai; prior to this, their origin is not precisely known. Later on, they are believed to be the settlers of Nanzhao (South-West China) and, as their empire declined, they moved south, to today’s Yunnan, North-East Burma, Laos, North Thailand and, down the Chao Phraya river, into Thailand’s central plains (more information in endnote [1]).

The Tai Dam people participated to this migration and established themselves in North Vietnam, founding a kingdom called “Sipsong Chu Thai”. Muang Thaeng, currently Dien Bien Phu, was their capital. During the French colonization, it was first incorporated into Tonkin, then into the autonomous “Tai Federation” and, finally, after the "Geneva Agreements", attached to the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. This community calls itself “Black Tai” (Tai Dam) in reference to their clothing, which, for the main part, is dark.

Tai Dam women in traditional black attire and embroidered headdress.

“Black Tai” women wearing a traditional embroidered headdress.

In the eighteens and nineteens century a part of the “Sipsong Chu Thai” population was displaced to populate Siam and, with the last century’s Indochina turmoil, many “Black Tai” fled their homeland and migrated to Laos, Thailand, or were granted asylum in the American state of Iowa. In Thailand, the early immigrants are usually called “Lao Song (Dam)”, while the newcomers, as in Ban Na Pa Nat, keep their “Tai Dam appellation”.

Tai Dam lady with black headdress.

The Tai Dam migration history is summarised on panels displayed at the “Ban Na Pa Nat” cultural centre [2]):

[SIC]: “In the 13thcentury, Nan Chao Dynasty was ended. Tai groups which were Tai A-hom, Tai Lao, Tai Siam and Tai Dam emigrated to other land, Tai Dam emigrated to Sip Song Chau Tai. In the 14thcentury, sip-song-Chau-Tai had the Ho pirates. In 1880, Tai Dam at Napanard village emigrated from the Ho pirates at the time of king Chulalongkorn (Rama v).

Tai Dam at Napanard village first immigrated to Thailand in 1880. Then they moved to Chiang Kwang and back to Thailand again in 1907 and settled in Napanard village in 1917.

Tai Dam at Napanard village immigrated from Muang Than (Dien Bien Phu Northwest of Vietnam). They settled temporarily village at Tung Sanam Chang, Ban Mee district, Lopburi province. In 1887, they immigrated to Sip-Song-Chau Tai by French requesting, arrived at Chiang Kwang, Laos PDR. They were not comfortable with French colonie. They immigrated back to Thailand in 1907, and settled at Napanard village in 1917”

One of the information panels in Ban Na Pa Nat.

2. The Road to Ban Na Pa Nat

The Tai Dam village of “Na Pa Nat” is located in North-East Thailand’s Loei province. It is close to Chiang Khan, a lively Mekong rim village, at the crossroad of three itineraries. The first trail follows the Mekong, north from Nong Kai, the second drives straight down from Loei city and the third, the western itinerary, crosses the “Door of Isan” in Dansai and leads down to Tha Li (the border crossing to Laos), then along the Hueang and Mekong rivers.

A “Phi Ta Khon” mask greeting travelers at the “Door of Isan”, just before Dansai.

For travelers on motorcycles, but also for car drivers, the region offers a maze of exhilarating rollercoasters through tree covered hills and a wealth of coiling trails along rivers.

Rollercoasters down to Tha Li and Chiang Khan.

Rollercoasters down to Tha Li and Chiang Khan.

Lively Chiang Khan along the Mekong river rim.

Many visitors spend a night or two in Chiang Khan, to enjoy the Mekong river’s mood and for an evening ramble through the city’s lively walking street. It is also a convenient starting point for a call to the nearby Tai Dam village.

Sunset mood along Chiang Khan’s Mekong promenade.

Early evening along the Mekong rim

Strolling through Chiang Khan’s walking street

A lively city, particularly in the evening hours.

Chiang Khan’s illuminated walking street.

The Tai Dam village of Na Pa Nat is only twenty-six kilometres away from Chiang Khan’s city centre. The itinerary starts with six kilometres on Route 201 (toward Loei), followed by twenty kilometres on provincial Route 3011.

Intersection of Route 201 and Route 3011 toward Ban Na Pa Nat.

3. Tai Dam House of Museum.

The first point of interest, when arriving in Ban Na Pa Nat is a cultural showcase: “The Tai Dam house of Museum”. It is one of the four places in the village built up to keep the culture alive for the next generation and promote it to visitors; they all feature weaving demonstrations and traditional buildings.

Now-a-days, this village has about five hundred inhabitants whose ancestors immigrated, more than one hundred years ago. After misfortunes in nearby hamlets, they finally choose a place located near to a forest of crabapple trees (nat trees) who have a camphor smell, disliked by spirits; actually, “Ban Na Pa Nat” literally means “the village near to the crabapple forest” [3].

Even so they originate from the same ethnic group, and region, the people of Ban Na Pa Nat are distinct from the “Lao Song (Dam)” of other Thai provinces. The latter arrived in the eighteens and nineteens century, particularly under the reign of king Chulalongkorn (Rama V) and were forced to populate Siam. The dwellers of Na Pa Nat arrived more recently, after the Indochina turmoil; they were able to keep their traditions largely alive and are known under their original name “Tai Dam”. Some of these settlers still have relatives in North Vietnam.

Modernization and economic growth take heavy tributes on traditions, particularly in smaller communities. While Thai-ness was promoted as an acculturation process, efforts are made, these days, to save the eroding cultural heritages. These are not only touristic assets but indispensable identity markers, linking individuals and groups to their roots.

The Tai Dam community in Na Pa Nad is committed to keep alive part of their culture, traditions and believes, providing a unique insight for visitors. Travelers to this village are not always aware of ethnic treasures on display, not only in form of antic artefacts and buildings, but through actual performances in daily life, ceremonies and festivals.

Billboard and main museum building at the “Tai Dam House of Museum”.

Some practices are common to most Tai groups. For instance, the houses used to be made with bamboo, covered with tree leave roofs, and were built on stilts; wetland rice cultivation provided the main staple and clothing was made by weaving cotton. Contemporary dwellings are more and more built with bricks, rice remains important, but in all communities, clothes, for daily use, are seldomly produced locally.

The aim of Na Pa Nat dwellers is to keep, as much as possible, their cultural heritage and traditions in their modern life. However, ancient houses are now only built as showrooms or “homestay” lodgings, while skilled weaver still produce cotton and silk artworks, traded to bring some revenues.

Small Tai Dam traditional constructions reproductions.

Tai Dam rice storing buildings.

Upper room of a traditional Tai House, now used as a museum.

A “Black Tai” lady wearing a traditional dress.

A Tai dam lady in a traditional attire.

The clothes play important roles in the Tai Dam’s ethnic identity. The group’s name refers to their custom to wear black attire, a society identification mark, a link to the ancestors and a sign of recognition when reaching “Muang Fa”, their heavenly realm. Silver adornments are also part of the costume, for instance earrings, hairpins, necklaces and belts.

A traditional “Black Tai” silver “butterfly clasp”.

An embroidered headdress scarf, the main colour spot in a Tai Dam women’s dress.

4. Weaving group “hamlet 12”

Another point of interest, in Ban Na Pa Nat is the “Weaving Group Center of Hamlet 12” (Moo 12). The place features some traditional buildings, a weaved cloths shop with an exhibition and a couple of wooden frame looms used by skillful women to produce silk and cotton pieces of art. Here, this important craft is kept alive while allowing dwellers to earn an income. The survival of this handiwork depends on its commercialization, on the possibility for the next generation to earn a living through it, and the readiness to embrace this artisanal profession.

Entrance to “Moo 12 Weaving Group”.

Khun Pa Pen, the most skilled Tai Dam weaver in Na Pa Nat.

Khun Sopha, a skilled daughter of Khun Pa Pen, working on a frame loom.

Khun Wipa, another member of the famous Na Pa Nat weaving family.

The traditional Tai Dam weaving tools are “frame looms”. The family in hamlet 12 is highly skilled and able to produce pieces with as many as 50 lines. The silk artwork on the loom, at the time of my visit, had 25 lines, a high weaving density, with a daily output of only thirty centimeters. The finished product, a special order for an American actress, will have a length of four meters. The daily output, for the even higher density weavings of 50 lines, is just twelve centimetres.

A 25 lines piece of art in progress, weaved on a frame loom by Khun Sopha.

Detail of the weaving piece in production, the red needle head shows the scale of the pattern.

The “Tai Dam flowers” are traditional decorations with protective powers. They are made out of shiny yarns and bamboo sticks, in various shapes. The cube brings good fortune, but the most popular form is the “Tum Noo Tum Nock” (mouse and bird box), shaped like a house, and used to protect dwellings from evils. They are usually mounted as mobiles, in different sizes.

Colorful yarn and bamboo decoration (Tai Dam flower).

A disappearing craft is the handweaving of baskets, which, in the past was the competence of men. In Na Pa Nat, plaited objects are no longer produced permanently, but demonstrations might be organized during festival times.

A Tai Dam man plaiting a colourful basket.

5. The annual brotherly reunion

The third place of interest is the village is the “Tai Dam Cultural Center”, opened in 1996 to preserve and showcase the “Black Tai” traditions and way of life.

On April 6th, every year, the Ban Na Pa Nat community organizes a festival called “Fraternal Tai Reunion”, inviting acquaintances and visitors to celebrate in a traditional way and to fulfill rituals for ancestors and spirits. This date was chosen to coincide with the “Chakri Day”, a national holiday in Thailand, allowing more people to participate to the venue.

During the morning, stalls are setup, collective food is prepared, and the place is arranged for the festival. Games are also organized for children and weavers demonstrate how to spin cotton threads, while small makeshift shops sell local products.

The center of the festivities is the “Ton Pang” a tree adorned with a variety of flashy mobiles featuring the traditional Tai Dam decorations in various shapes; they are globally called “flowers” (dok mai Tai Dam).

A decorated tree (Ton Pang) marks the center of the festivities place.

The traditional “Black Tai” decorations, the “Tai Dam flowers”, are omnipresent.

The first activities during the morning, are children’s games and competitions, like walking on stilts and throwing cloth balls through a suspended figure eight target (tot ma kon).

Kids in Tai Dam dresses play around the festival compound.

Walking on stilts, a children’s game.

Throwing cloth balls through a target (tot ma kon), a competition for kids and adults.

Tai Dam girls performing traditional dances.

The official opening is at noon, usually with the presence of high ranking representatives from the province and, as in 2018, the presence of “Miss Grand Thailand Loei 2018”, a charming crowned princess, available for selfies or children’s group pictures.

Speeches and other performances are presented on a podium or on the central place, around the decorated pole (Ton Pang).

Opening ceremony on the podium.

Opening ceremony and speeches.

The podium also serves as a catwalk for “Black Tai” dwellers in traditional attire.

The rhythms accompanying Tai Dam music and dances, are produced by large hand-held bamboo trunks, hit on floor planks; these cavernous sounds are echoed by percussions on metallic gongs.

Tai Dam ladies with rhythmic bamboo trunks.

A line of “Black Tai” ladies holding bamboo trunks.

Colorful stitched Tai Dam headdress.

“Black Tai” ladies in traditional attire.

Tai Dam ladies on stage.

On stage with a traditional headdress.

“Black Tai” ceremony on the central place.

Group pictures on the central place.

“Miss Grand Loei 2018”, a charming crowned princess.

Miss Grand Loei 2018 – visiting the “Black Tai” venue.

In the early evening, a parade is organized along the village’s main road. It is a slow-moving cortege, as many participants are dancing all along the way.

Dancing “Black Tai” pageants.

Tai Dam cortege participants.

Sitting on decorated chariots – a relaxed way to attend the procession.

Tai Dam ladies sitting on a parade chariot – they wear black tube-skirts with a traditional watermelon pattern (sin taeng moo).

A young pageant hanging on his mother’s back in a traditional way.

Finally, the cortege reaches the festival place, and the rest of the evening is devoted to traditional dances around the decorated tree (Ton Pang).

Traditional dances on the on the central place.

6. people and traditions

The Tai Dam people of Ban Na Pa Nat are committed to maintain whatever possible from their cultural heritage. Compared to other ethnic groups, they have done well and are recognized for this achievement. This is, however, not an easy endeavour as, for many years, integration and acquisition of Thai-ness was the political aim.

Development and modernity are, nowadays, the eroding factors for traditions; in order to make choices and to increase the economic levels, external exposure and knowledge acquisition is necessary. Particularly youngsters are leaving the community for environments were uniformization is required. Currently, western type habiliments are the norm, not only to dwell outside but also in the village itself. Clothing remains an important identity marker for the Black Tai, a link to their roots and ancestors, as well as a recognition sign for the next realm; in Ban Na Pa Nat the villagers still take many opportunities to wear their traditional attires, for special festivities, as it is the case for the annual “Fraternal Tai Reunion”.

The clothes play important roles in the Tai Dam’s ethnic identity. The group’s name refers to their custom to wear black attire, a society identification mark, a link to the ancestors and a sign of recognition when reaching “Muang Fa”, their heavenly realm. Silver adornments are also part of the costume, for instance earrings, hairpins, necklaces and belts

Traditional “Black Tai” attire

Colorful stitched scarf headdress

Despite common roots, the Tai Dam language is quite different and not mutually intelligible for central Thai inhabitants. In addition to their own idiom, youngster have to learn “central Thai” (at school) and probably some Isan language (Lao). In the village itself the Tai Dam language is still widely spoken.

Group picture in various outfits.

Tai Dam lady in traditional attire.

Tai Dam lady in traditional attire.

The specific Tai Dam script, is rarely used now. Seen from afar it shows similarities with the Thai or Lao scripts; it is, however, totally different and illegible for untrained eyes.

Tai Dam lady in traditional attire.

Tai Dam lady in traditional attire.

Young Tai Dam girl.

Hair is an important feature for “Black Tai”, they keep it long and tie it into knots indicating their marital status.

Tai Dam ladies preparing their hair for the festival.

When I go back to villages that I have visited in the past, I print some pictures and give them to my former “models”. I did this in Na Pa Nat and handed out photographs taken the year before.

Group of young “Black Tai” girls with pictures from last year.

A young Tai Dam girl, together with a friend, holds her picture from last year.

7. Beliefs and funerals

In their homeland, in North Vietnam, the Tai Dam are mostly animist, a differentiation from the other Tai groups. In Ban Na Pa Nat this has to be put in perspective as, currently, a majority of the inhabitants are nominally Buddhists, with a small number of Christians. Nevertheless, and as it is the case in other communities in Thailand, Brahmanism, animism and ancestral worship are intermingled in daily life’s practices. Spirits (phi) still play an important role in Thailand’s folk imagination; this is the case in the “Black Tai” community with animism and Brahmanism being very present.

During one of my visits to Na Pa Nat, I was invited to participate in a traditional funeral, and was advised that it would be similar to a Christian ceremony.

The traditional Tai Dam funerals are officiated by a shaman (moo phi) [4] and the corpses are entombed in a sacred forest near to the village. A walking cortege of dwellers, family and friends of the deceased, process toward the burial place, with, these days, a pick-up truck transporting the coffin.

The funeral procession led by the shaman from the village to the sacred forest.

Once the Shaman has defined the precise burial place, villagers take turns to excavate a pit, about as deep as a standing person.

Villagers taking turn to excavate a pit.

As the soil is sandy, the work is progressing rapidly.

The pit is about the depth of a standing person.

Last inspection of the pit by the shaman.

Friends and relatives are waiting near to the excavation work.

Relatives with a picture of the deceased loved one.

The “Black Tai” cultural link to their clothing remains behind their death. The deceased person is dressed in its Tai Dam attire for his burial, in order be recognized in “Muang Fa”, their heavenly realm.

The corpse is displayed one more time, allowing relatives to bid a last farewell, and spray holly water on the deceased face.

The burial procedure is supervised by the shaman.

A relative at the burial place.

After the funerals, the deceased spirit is invited to dwell into a special room (Ancestor’s Room), located in the residence house.

In the museum: explanatory board written in Thai and English – the second line is “Black Tai” script.

------------

Notes:

[1] The Tai origin and migration history is more complex and uncertain than outlined in my shortcut. In contrary to the Chinese history, no written early Tai chronicle exists, and the oral transmission, often legendary, leaves many points unclarified. It seems, however, that the Tai and Chinese shared common roots which, for unknown reasons, split in different directions.

The early Tai societies were organized in “muangs”, small people conglomerates, normally located in a single valley and led by a chieftain. With the time, some “muangs” gained strength, were able to build alliances with neighbors, and, finally, became principalities or kingdoms. The shape and fate of these larger entities was molded by their own strength and ambitions, but also through geopolitics, like the Mongol invasions, the activities of Haw bandits, the Burmese and Khmer war appetites, the developments of China, and finally, the French and British colonial occupations and their backlashes.

This sketchy historical shortcut is only meant to put the global Tai migrations into a frame. Nowadays, Tai ethnic people are found, in various percentages, in Thailand, Laos, Burma, Vietnam, China and Northeast India. In Thailand and Laos they are the majority of the population while in other countries, their former kingdoms were integrated, leaving them as national minorities (Shan, Tai Lue, Black Tai, Puan, …)

[2] [SIC] this is the original text transcription, only slightly adapted for gross language mistakes.

[3] Wikipedia: Blumea balsamifera is a flowering plant belonging to the Blumea genus, Asteraceae family. It's also known as Ngai camphor and sambong (also sembung). In Thai folklore, it is called Naat (หนาด) and is reputed to ward off spirits.

[4] I use the name “shaman” as it is the most common for Westerner. Actually, in this case it is a “Mo Phi” which translates as “(spirit) priest”. The Tai Dam have a whole hierarchy of religious practitioners, who, usually transmit their powers and knowledges in a hereditary lineage. The actual Tai Dam Shaman is called “Mo Mod”.

Some literature:

Tai Groups of Thailand

Volume 1 Introduction and Overview

Joachim Schliesinger

2001 White Lotus, Bangkok

The Thai Ethnic Community in Viet Nam

Cam Trong

The Gioi Publishers 2007, Vietnam

Dress and Identity among the Black Tai of Loei Province Thailand

Franco Amantea

Thesis Bachelor of Arts, Simon Fraser University 2003

D002

D002